It was weeks before the result of the 2024 presidential election that Shapiro was advertised “to bring a dose of facts and reality to four campuses in desperate need of true intellectual diversity.” At UCLA, Yale, Cornell, and Vanderbilt, Shapiro offered “to break up the left’s monopoly on ideas” and deliver them “truth and sanity.” He was insisting on a divide between America and its colleges.

CREDIT: BILLY STAMMER / COLLEGETOWN

Many universities stand behind self-declared institutional neutrality, but the vast majority of America’s elite colleges emphasize progressive social causes. They champion tolerance, gender affirmation, safe spaces, diversity, equity, and inclusion—which, according to last year’s election results, the majority of voters oppose, particularly those without a college degree. Deemed a “diploma divide,” the Democratic Party had lost ground with non-college-educated voters.

“We spend more money on higher education than any other country, and yet they're turning our students into Communists and terrorists and sympathizers of many, many different dimensions,” Trump stated in a campaign advertisement in late 2023. Trump offered “something dramatically different,” and by the time Shapiro spoke at Vanderbilt, he had just won the popular vote.

At the helm of Vanderbilt’s Langford Auditorium, Shapiro declared the end to an “age of stagnation” and an “age of moral confusion.” “I don't think that the election was so much about President Trump,” he told the crowd of students, “as much as it was about the American people who were just done.”

.JPEG)

CREDIT: BILLY STAMMER / COLLEGETOWN

Behind these words, weaponized on yet another group of “whiny, entitled snowflakes,” did Shapiro—who was campaigning for Trump—have the majority of Americans behind him? This time around—in his near-decade-long career of collegiate speaking gigs—was he right? Last election, did the American people vote against the values of their elite institutions?

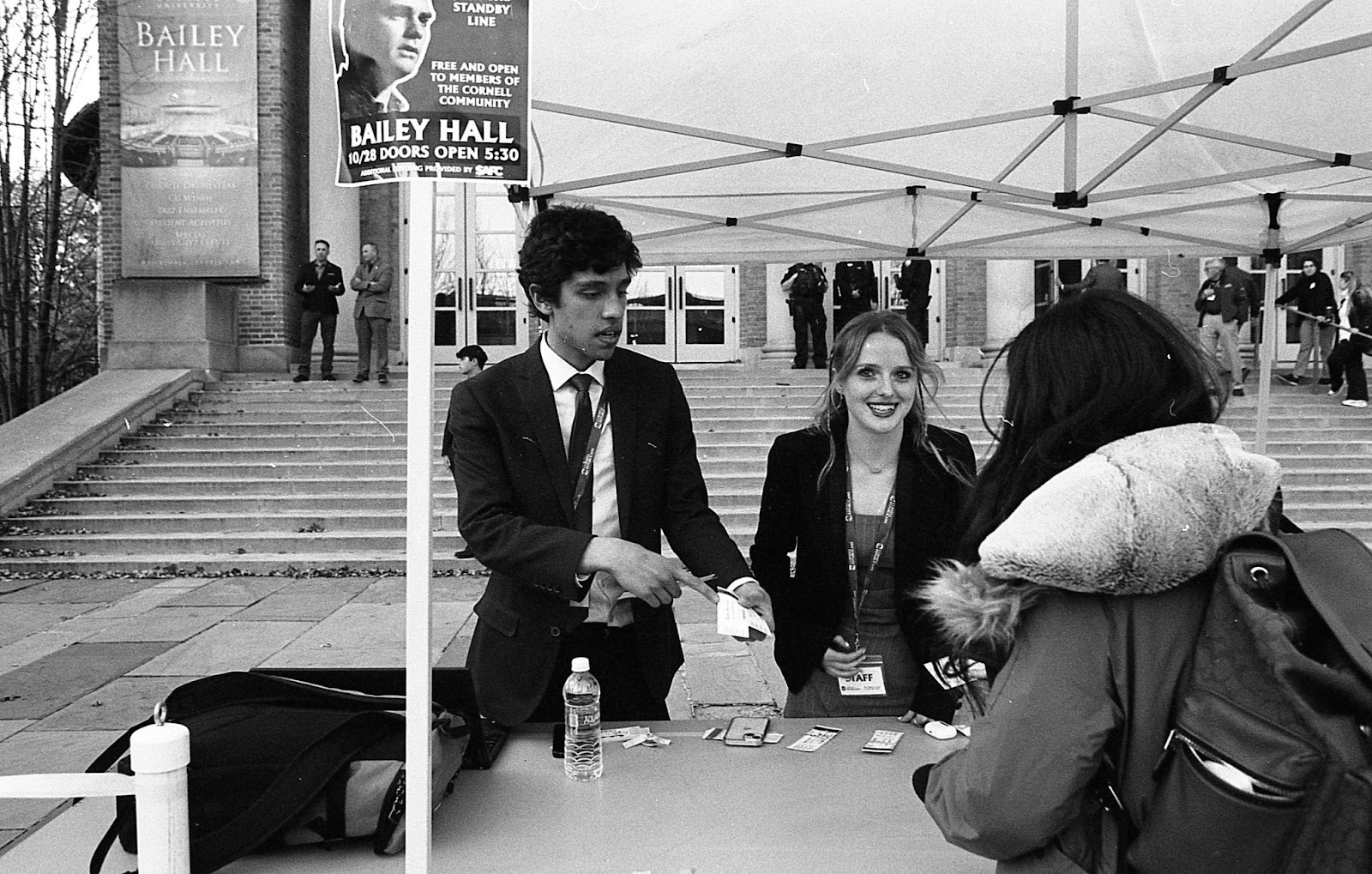

A few weeks before the election, Shapiro ushered in that feeling of divide. University police guarded Cornell’s Bailey Hall and officers escorted individual event-goers as they walked up a set of stone steps. A crowd of students with signs stood in the background; it was a scene plagiarized from the Little Rock Nine, albeit with conservatives escorted as the agitators of change, and with campus cops protecting them instead of National Guardsmen. It felt like something was happening, something unignorable. Trump was leading in the October polls.

CREDIT: BILLY STAMMER / COLLEGETOWN

Inside the auditorium, a few teams of EMS walked the halls and armed sentries stood by the doorways. A production crew adjusted lighting and constantly swiveled a crane with a TV camera. As screechy rock music sounded over the speakers—complete with foot stomps and tambourine smacks and electric guitars—you had the feeling that you were on the edge.

CREDIT: BILLY STAMMER / COLLEGETOWN

When Shapiro entered, he was met with a heavy, cathartic round of applause—a mix of irony and hatred and spectacle and support. At the stereotypical liberal university, Shapiro began his speech by declaring, “Intersectional wokeness must die!” He went on to reprimand America's elite institutions and their “wokeness,” “transgenderism,” and various forms of brainwashing, coddling, and complaining. Then, he took questions from his audience of students.

As Shapiro arrived at Yale, weeks earlier on the anniversary of October 7, Richie George, a writer for The Yale Herald, prefaced the event with a prophecy. “This is how I think it will go,” he wrote: “Inflammatory speech prompts impassioned questions with even more incendiary responses––looped into a destructive cycle of inflammation.” George continued: “Every view, every comment, every like, every slur, every defense, every attack, and every mode of engagement are tools for his survival. Ben Shapiro speaks at Yale for his survival.”

By the time the conservative firebrand arrived at Vandy, he wasn’t just surviving; He was gloating. It seemed he had won; the colleges had lost; the American public was on his side… and yet, he would only take “controversial” questions from the audience of college students.

.JPEG)

CREDIT: BILLY STAMMER / COLLEGETOWN

Months after Ben Shapiro’s college tour, as Trump’s executive orders reigned down on schools running DEI initiatives, teaching critical race theory, and harboring “pro-Hamas aliens and left-wing radicals,” Cornell student Anna Loy looks back on the speaker that seemed to preface it all. “Speaking tours like his in the fall—they're like the foot soldiers for the larger MAGA movement,” she says.

At the event, Loy asked Shapiro to explain both his support of free speech and yet also the banning of certain books. Shapiro had replied that Cornell alumna Toni Morrison—the first Black woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature—“is one of the most overrated authors of our time.” (“I just couldn't resist,” he explained.) Then, Shapiro arrived at the moment he was waiting for: He snapped at Loy, “I think it's fiction when you say boys are girls and girls are boys.” Amid heavy applause, the camera crane quickly swiveled; she became Shapiro’s opponent in a spliced-up YouTube Short that appeared that very night.

This spring, Loy, a government major, is taking a course on Black political theory. “And to think that classes like that would likely fall outside of what the Trump administration thinks should be taught in schools”—Loy says—“I think it’s pretty scary.” She says Shapiro “served to rile up young voters, which proved to be a big part of Trump's win.”

Long after Shapiro’s tour and Trump’s inauguration, I ask José Toledo-Alvarez about any after-effects. Last fall, in the midst of the crowd at Bailey Hall, while his legs nervously shuck beneath him, Toledo-Alvarez told Shapiro that he disagreed with him—that the speaker’s act seemed “to divide more than anything.” With declarations, funding freezes, and executive orders adrift in our conversation in the spring, he says, “It’s polarizing, it’s divisive, it’s intensifying.”

Richie George says that his prediction was right—that Shapiro’s college tour “revolved around really kind of banal semantic debates.” He stresses that “it wasn't doing anything.”

“This is a wider problem where we substitute meaningful social discourse that taps into the problems that our country is facing with ineffectual, simple, easy appeals to people's senses. It's a deeply sensational type of discourse,” he says, “that I feel is really unproductive.”

George told his friends not to go to Sheffield-Sterling-Strathcona Hall, but Shapiro’s speech at Yale—and every other school he visited—was packed.

CREDIT: BILLY STAMMER / COLLEGETOWN

Now, the Herald writer asks, “in the face of Trump, are people realizing that that politics is actually very damaging?” He says that people will recognize that, “if you actually take whatever Trump and what Shapiro gesture to, it actually causes bad outcomes. And I think that luckily will cause the discourse to shift differently,” he tells me, offering another of his predictions. “But I think it actually is time for us to sit with, like, wow, this is appealing. This is a thing that people like.”

During Shapiro’s Q&A at Cornell, one student had asked how his combative, sensational speech aligned with what he wanted to teach future generations. “I'm not going to apologize for the business being the business,” he said smiling. “I didn't make the rules. We're just really good at the game.” Then, Bailey Hall roared with applause. ⬥

.png)